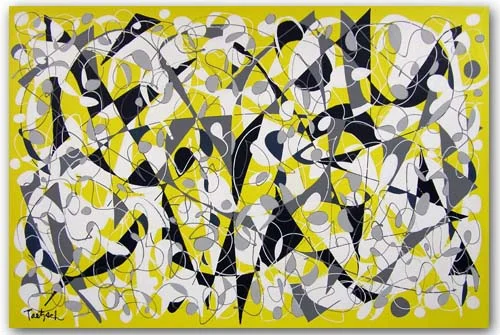

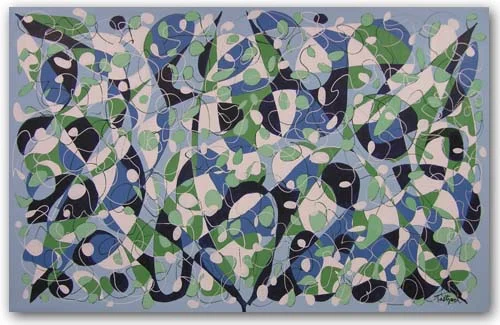

This new painting evolved over many steps with the application of layers of acrylic paint. I first worked on a background which consisted of blending a number of colors very loosely with a wet brush:

Signs and Signals, Step 1

The next two steps involved drawing lines of color across the canvas--first with one orientation, then turning the canvas 90 degrees and drawing more lines.

Signs and Signals, Step 2 and 3

In the next stages of the process, I began filling in some of the shapes that were created by the intersecting lines. I used a pale beige, very pale yellow, dusky green, teal, and a reddish orange. These painted sections then popped forward from the background, providing a path for the eye to follow.

Signs And Signals, Step 4

At this point I wasn't sure what I wanted to do, but took the plunge and added some texture by drawing straight, zig-zag, and circular lines on several sections of the canvas.

Signs And Signals, Step 5

Now I had no idea what to do next. I liked what was there so far, but the painting still felt "unfinished" to me. So I took a radical step. I mixed the pale yellow with water and gloss medium to make it translucent, and then painted over large sections of the canvas. Next, I dipped my brush into a thin, light teal and brushed that on the swirls inside the circular shapes. I also added it in zig-zag lines across some of the other shapes.

Finally, I took a deep cadmium red and drew somewhat random lines across the canvas. Wow. This turned out to be a painting unlike any I'd ever done! Here it is: Signs And Symbols.

Signs And Signals, Step 6